Rising fertiliser and food prices raise concern over food security, who will be spared?

Rising fertiliser and food prices raise concern over food security, who will be spared?

Everyone has a plan ‘till they get punched in the mouth. This frequently cited quote by Mike Tyson gains more relevance today. Politicians may aspire with plans to increase their odds of being elected. Greening economy projects, waging war against inequality, exerting political dominance over other countries, and other populist policies are some of the examples. However, all these means nothing if their leadership fails to bring food on the table.

In our past blog (link), we pointed out how supply chain issues, tight agriculture market, energy crisis, and geopolitical tension crystallised in the great rally of ammonia and fertiliser prices. If we consider the factors at play, this might be the warning shot of an upcoming food crisis.

Skyrocketing food prices have been associated with social unrest and we are at all-time high

It is pretty straight forward why high and volatile food prices could destabilise a society. Food is both essential and have a significant share of our daily spending. Based on 2018 Euromonitor data, food on average accounted for 28.7% of consumer spending in 51 countries throughout the globe. For some countries like Bangladesh, Myanmar, Kenya and Ethiopia, this figure can be as high as 53% to 59% .

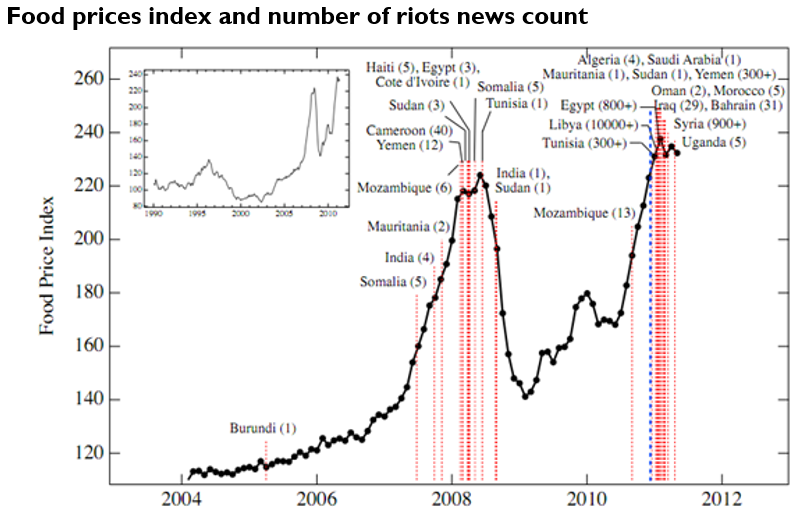

There are anecdotal evidence in the past whereby food problems led into social unrest. In 1789, the famine led French peasants to storm the Bastille prison and ended up overturning the French empire. In the modern era, the high food prices in 2008 and 2011 sparked numerous civil unrests in the Middle East.

Before the recent boom, commodities were the sucker’s bet of the last decade. At the start of its gracious fall in the 2010s, the substantial commodity investments in the 2000s left the world with abundant stocks of commodities. This time around, the prolonged relaxed financial conditions and minimum investments in this sector drift the world into the opposite setting. There is a lot of liquidity, yet so few goods.

If we consider commodity as a currency of its own, we are seeing where Gresham’s rule of bad money drives out good money in action. The rapid expansion of liquidity without a respective production expansion of commodities led to the appreciation of the latter.

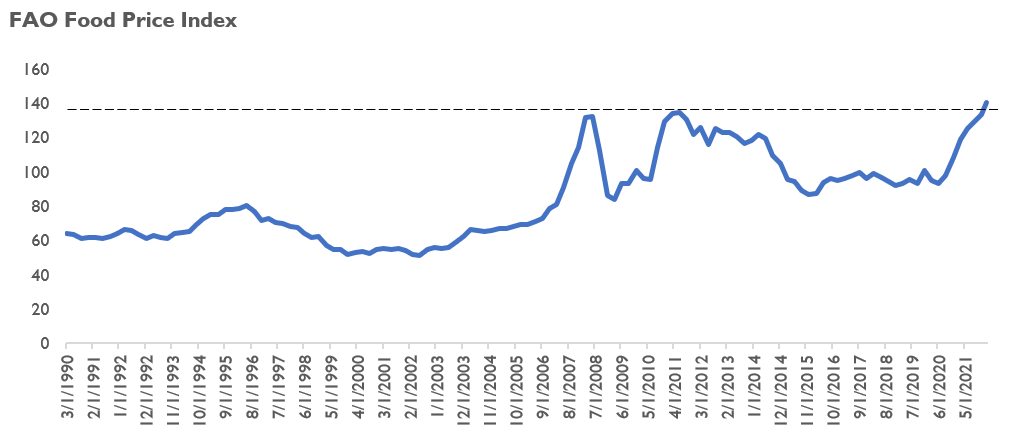

Today, food prices already exceeded the highs of 2011 and are yet to lose their steam.

Countries are taking food protectionism measures to stabilise domestic food prices

We find the severity of the potential food crisis cannot be underestimated. Case in point would be the magnitude of Russia-Ukraine war in escalating this matter.

Both Russia and Ukraine play significant roles in the agriculture or fertiliser market. Russia is the biggest exporter of wheat (18% of global export) and a major exporter of sunflower oil (18% of global export) and fertilizers (20% of global ammonia export). On the other hand, Ukraine is also a major exporter of wheat (15% of global export) and the biggest sunflower oil exporter (37.5% of global export).

The prolonged Russia-Ukraine conflict adversely impacts both near and long-term supply. Near-term supply has been affected because of the logistical hurdles made by the war. The future supply is at risk because Ukraine might miss this spring planting season. The ramifications of sudden drop in food exports at a time of tight stock will be painful and costly to bear by the rest of the world.

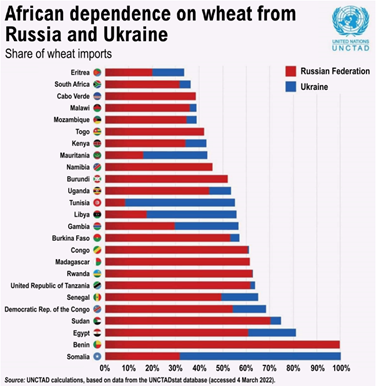

For some countries, such as those in the African continent, food affordability and availability will become major issues. From the following graph, we could see how Russia and Ukraine war could jeopardise the procurement of wheat in Africa.

This concern over food insecurity gained the spotlight in the world’s most populated country, China. During the 13th National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference on 7 March 2022, China President Xi Jinping underscored the importance of food security and ordered greater self-reliance in its production. Below was his speech as quoted by South China Morning Post:

“Vigilance in food security must not slacken, we must not think that food ceases being an issue after industrialisation, and we cannot count on international supplies to solve the problem… We must plan ahead by adhering to the principles of domestic production and self-reliance while ensuring an appropriate level of imports and technology-backed development… the rice bowls of the Chinese people are filled with Chinese grain”

There is no smoke without fire. The mounting food security risk is even more visible with the spreading food protectionism measures. China, Russia, Ukraine, Algeria, Hungary, Moldova, Turkey, Egypt, Serbia, and Indonesia are growing list of countries that curbs food or fertiliser exports.

A resource-rich country like Indonesia may fare better in facing a food crisis

Indonesia has adequate resiliency in the mounting food insecurity globally. In terms of food production, the country is well-known to have a 59% share in global palm oil production. This vegetable oil is extremely efficient. Palm oil supplies 40% of the world’s vegetable oil demand with only 6% of land used for vegetable oils. These economics made the commodity simply irreplaceable.

Furthermore, the USDA ranked Indonesia as the fourth biggest producer of rice with a 7% global market share. This country is also ranked the twelfth largest producer of corn with 1% global market share.

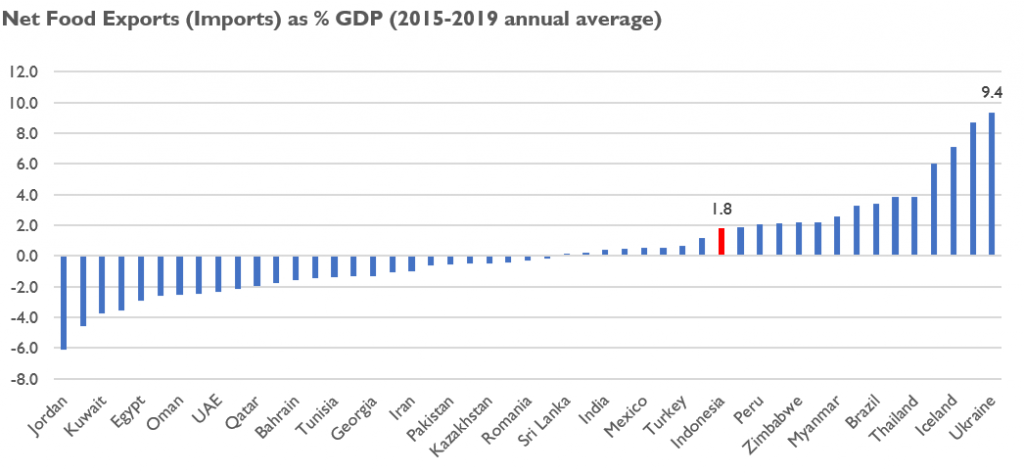

Given this natural advantage, Indonesia is inherently a net exporter of foods. The skyrocketing price of global food prices would suggest that the country will see its surplus widen. As such, Indonesia should benefit from either relative resiliency in inflation or a widening trade surplus.

According to The Economist’s research on the food security index 2021, Indonesia ranked 37th of 113 countries globally in terms of the availability of food supply. Ample land for production, low volatility of production, and strong food security policies and agency are reasons why Indonesia fared well on this subject.

Furthermore, Indonesia’s food security improvement between 2012 and 2021 ranks 24th among world countries. Based on our past on-the-ground observation, infrastructures development and strengthening of food security policies and enforcement are the reasons for the improvement. We discussed more detail about Indonesia infrastructure development in our Q1 2019 report (link).

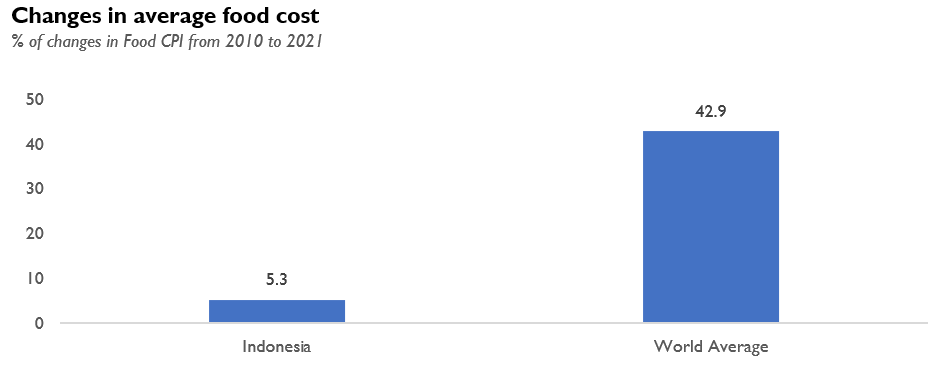

We think that Indonesia’s resiliency in food security is pretty much reflected in the marginal food cost increase relative to the global average from 2010-to 2021.

In the world of commodities shortage and abundant liquidity, those who own the former will stand to benefit. Besides food, Indonesia produces lots of commodities and has been regarded as resource-rich land for decades. How will the booming commodity market affect Indonesia? How it be different this time? Stay tuned to our blog!

Admin heyokha

Share

Everyone has a plan ‘till they get punched in the mouth. This frequently cited quote by Mike Tyson gains more relevance today. Politicians may aspire with plans to increase their odds of being elected. Greening economy projects, waging war against inequality, exerting political dominance over other countries, and other populist policies are some of the examples. However, all these means nothing if their leadership fails to bring food on the table.

In our past blog (link), we pointed out how supply chain issues, tight agriculture market, energy crisis, and geopolitical tension crystallised in the great rally of ammonia and fertiliser prices. If we consider the factors at play, this might be the warning shot of an upcoming food crisis.

Skyrocketing food prices have been associated with social unrest and we are at all-time high

It is pretty straight forward why high and volatile food prices could destabilise a society. Food is both essential and have a significant share of our daily spending. Based on 2018 Euromonitor data, food on average accounted for 28.7% of consumer spending in 51 countries throughout the globe. For some countries like Bangladesh, Myanmar, Kenya and Ethiopia, this figure can be as high as 53% to 59% .

There are anecdotal evidence in the past whereby food problems led into social unrest. In 1789, the famine led French peasants to storm the Bastille prison and ended up overturning the French empire. In the modern era, the high food prices in 2008 and 2011 sparked numerous civil unrests in the Middle East.

Before the recent boom, commodities were the sucker’s bet of the last decade. At the start of its gracious fall in the 2010s, the substantial commodity investments in the 2000s left the world with abundant stocks of commodities. This time around, the prolonged relaxed financial conditions and minimum investments in this sector drift the world into the opposite setting. There is a lot of liquidity, yet so few goods.

If we consider commodity as a currency of its own, we are seeing where Gresham’s rule of bad money drives out good money in action. The rapid expansion of liquidity without a respective production expansion of commodities led to the appreciation of the latter.

Today, food prices already exceeded the highs of 2011 and are yet to lose their steam.

Countries are taking food protectionism measures to stabilise domestic food prices

We find the severity of the potential food crisis cannot be underestimated. Case in point would be the magnitude of Russia-Ukraine war in escalating this matter.

Both Russia and Ukraine play significant roles in the agriculture or fertiliser market. Russia is the biggest exporter of wheat (18% of global export) and a major exporter of sunflower oil (18% of global export) and fertilizers (20% of global ammonia export). On the other hand, Ukraine is also a major exporter of wheat (15% of global export) and the biggest sunflower oil exporter (37.5% of global export).

The prolonged Russia-Ukraine conflict adversely impacts both near and long-term supply. Near-term supply has been affected because of the logistical hurdles made by the war. The future supply is at risk because Ukraine might miss this spring planting season. The ramifications of sudden drop in food exports at a time of tight stock will be painful and costly to bear by the rest of the world.

For some countries, such as those in the African continent, food affordability and availability will become major issues. From the following graph, we could see how Russia and Ukraine war could jeopardise the procurement of wheat in Africa.

This concern over food insecurity gained the spotlight in the world’s most populated country, China. During the 13th National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference on 7 March 2022, China President Xi Jinping underscored the importance of food security and ordered greater self-reliance in its production. Below was his speech as quoted by South China Morning Post:

“Vigilance in food security must not slacken, we must not think that food ceases being an issue after industrialisation, and we cannot count on international supplies to solve the problem… We must plan ahead by adhering to the principles of domestic production and self-reliance while ensuring an appropriate level of imports and technology-backed development… the rice bowls of the Chinese people are filled with Chinese grain”

There is no smoke without fire. The mounting food security risk is even more visible with the spreading food protectionism measures. China, Russia, Ukraine, Algeria, Hungary, Moldova, Turkey, Egypt, Serbia, and Indonesia are growing list of countries that curbs food or fertiliser exports.

A resource-rich country like Indonesia may fare better in facing a food crisis

Indonesia has adequate resiliency in the mounting food insecurity globally. In terms of food production, the country is well-known to have a 59% share in global palm oil production. This vegetable oil is extremely efficient. Palm oil supplies 40% of the world’s vegetable oil demand with only 6% of land used for vegetable oils. These economics made the commodity simply irreplaceable.

Furthermore, the USDA ranked Indonesia as the fourth biggest producer of rice with a 7% global market share. This country is also ranked the twelfth largest producer of corn with 1% global market share.

Given this natural advantage, Indonesia is inherently a net exporter of foods. The skyrocketing price of global food prices would suggest that the country will see its surplus widen. As such, Indonesia should benefit from either relative resiliency in inflation or a widening trade surplus.

According to The Economist’s research on the food security index 2021, Indonesia ranked 37th of 113 countries globally in terms of the availability of food supply. Ample land for production, low volatility of production, and strong food security policies and agency are reasons why Indonesia fared well on this subject.

Furthermore, Indonesia’s food security improvement between 2012 and 2021 ranks 24th among world countries. Based on our past on-the-ground observation, infrastructures development and strengthening of food security policies and enforcement are the reasons for the improvement. We discussed more detail about Indonesia infrastructure development in our Q1 2019 report (link).

We think that Indonesia’s resiliency in food security is pretty much reflected in the marginal food cost increase relative to the global average from 2010-to 2021.

In the world of commodities shortage and abundant liquidity, those who own the former will stand to benefit. Besides food, Indonesia produces lots of commodities and has been regarded as resource-rich land for decades. How will the booming commodity market affect Indonesia? How it be different this time? Stay tuned to our blog!

Admin heyokha

Share