Déjà Vu All Over Again: Trump 2.0, Trade Wars, and the Rewriting of Global Trade Rules

Déjà Vu All Over Again: Trump 2.0, Trade Wars, and the Rewriting of Global Trade Rules

When the U.S. Dollar Index (DXY) dipped below the psychologically sacred 100 mark, the reaction across markets was immediate and biblical.

Bond yields erupted like a volcano no one had prepared an evacuation plan for.

Volatility rose sharply — not quite “end of the world” levels, but just enough to make traders double their coffee intake and triple-check their hedges.

Gold? Gold didn’t just rise — it strapped on a superhero cape, crashed through a few ceilings, and started flexing in slow motion.

It was, by all appearances, chaos.

And yet, there I sat—having gone through my second matcha in hand—deeply preoccupied with trying to figure out why my toast had burned on only one side.

Because here’s the thing: this wasn’t a heart attack. It was more like a long-overdue jog.

The dollar, after decades of indulgence, is simply trying to slim down. And trimming trade deficits, like trimming body fat, follows the same rule:

- Consume less than you expend

In trade-speak, that means importing less (or exporting more).

- Shed excess weight naturally

A modestly weaker dollar makes U.S. goods cheaper abroad

- Rebalance energy

Domestic factories and payrolls pick up the workload that overseas suppliers had been shouldering.

In that light, a weaker dollar isn’t a breakdown—it’s the feedback loop of a country attempting a strategic reset.

And behind that adjustment lies a bigger story: the U.S., under a Trump 2.0 presidency, is re-evaluating decades of trade dogma—not out of theory, but necessity.

Trump 1.0: Big Talk, Smaller Follow-Through

When Donald Trump took office in 2017, he promised to tear up “unfair trade deals” faster than a kid opens birthday presents.

NAFTA got rebranded as USMCA. Tariffs were slapped on China. Economists panicked.

But in practice?

- The U.S. trade deficit actually grew, from $481 billion in 2016 to $679 billion in 2020.

- Manufacturing jobs saw a brief lift before the pandemic pulled the rug out.

- The Phase One deal with China delivered photo ops but little systemic change.

Trump 1.0 was loud—but left the deeper structural incentives for offshoring intact.

Meanwhile, global rivals like China played a very different game.

The Richman Perspective: Free Trade’s Fine Print

Enter Balanced Trade (2014), by Jesse, Howard, and Raymond Richman.

We don’t quote it because it’s gospel—but because it captures how the U.S. might be viewing its predicament.

The Richmans argued that textbook free trade assumes everyone plays fair. But when countries embrace mercantilism, the game breaks.

Their key points:

- The U.S. hasn’t posted a goods & services surplus since 1976.

- Foreign reserves ballooned from $1.4 trillion (1995) to over $10 trillion (2013).

- America’s net international investment position flipped from +13% (1980) to –35% (2012).

And what’s more concerning: countries like China and Japan don’t spend those dollars on U.S. goods—they buy U.S. debt. As of early 2025, China holds $784.3 billion in Treasuries; Japan, $1.13 trillion. According to the Richmans, that’s not trade – that’s America exporting IOUs.

The Richmans suggest a “scaled tariff”—a self-adjusting levy pegged to bilateral deficits. Not protectionism per se, just a nudge to restore balance.

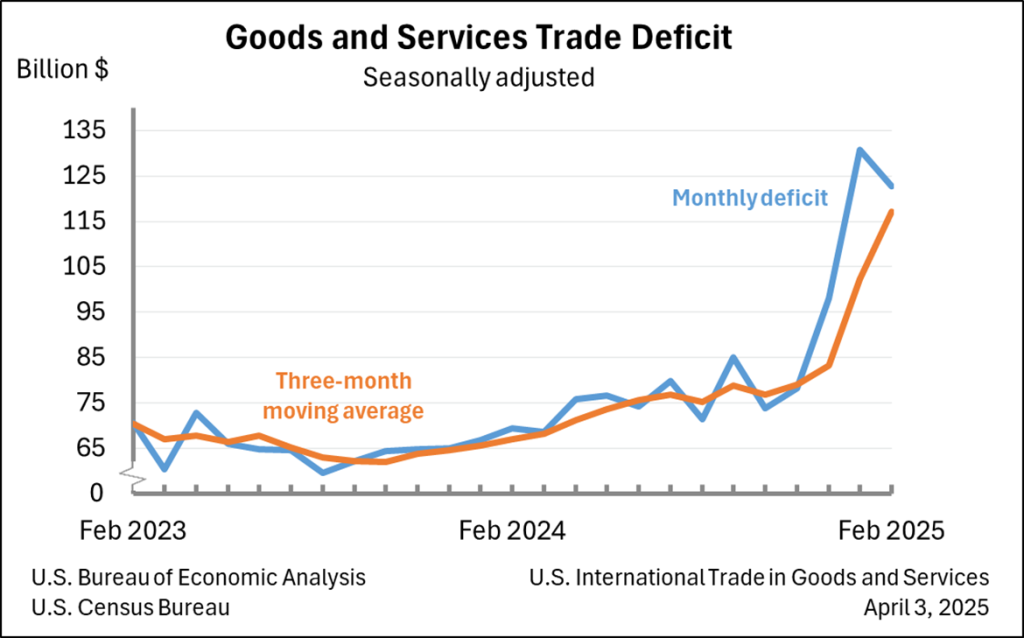

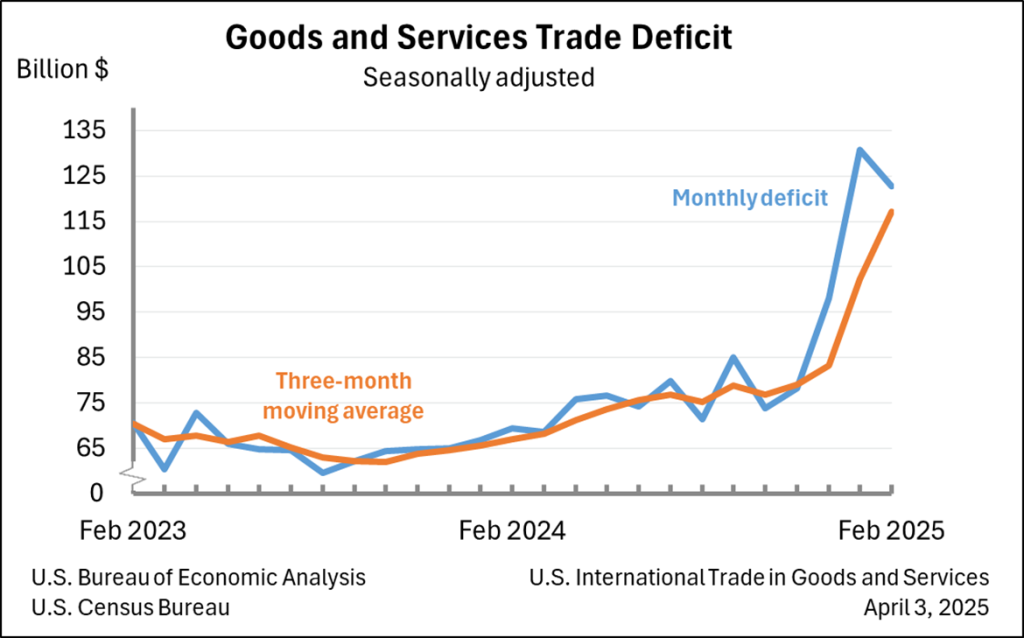

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis; U.S. International Trade in Goods and Service

But again, this is a lens, not the truth. And maybe that’s the deeper takeaway as written by this book:

The U.S. isn’t declaring trade broken—it’s trying to restore competitiveness in a world where others stopped playing by the book long ago.

Trump 2.0: Trade Policy With a Bit More Teeth

Fast-forward to today: Trump 2.0 is leaning hard into so-called “reciprocity”.

Not just at rallies, but across a Washington that’s increasingly skeptical of free-market purity.

What’s on the table:

- Targeted tariffs based on bilateral trade deficits.

- Challenges to WTO rules that limit U.S. retaliation.

- Industrial policy tied to national security, encouraging onshoring of critical supply chains.

Of course, nothing is free.

A Brookings Institution report estimated that the 2018–2019 tariffs cost American consumers $57 billion a year. But for many voters—and policymakers—some level of sacrifice now feels worth it.

Globalization might have been a perfectly beautiful idea, but according to the Richmans, it is far from perfect in reality.

Global Reverberations: Some Win, Some Whimper

If the U.S. doubles down on “balanced trade,” ripple effects will follow.

Potential Winners:

- Emerging markets: India, Vietnam, Mexico—likely alternatives to China in the new supply chain map.

- Commodities: Reshoring means higher demand for industrial metals, energy, and logistics.

- Selective U.S. sectors: Tech, pharma, and defense-related manufacturing.

Likely Losers:

- Export-reliant economies like Germany, South Korea, and Japan.

- Global investors navigating rising FX and bond volatility.

The IMF warns: if tariffs become widespread, global GDP could shrink by 0.5%.

Not world-ending, but not nothing either.

Food for Thought: Was Free Trade Ever Really Free?

The Trump 2.0 shift isn’t just about tariffs—it’s a symptom of deeper anxieties:

- If globalization weakens national resilience, is it still worth it?

- Can you really have fair trade, and what does fair trade rhetorically even really mean?

- Is consumption-driven growth sustainable when you’ve outsourced everything?

The Richmans’ thesis? Free trade without balance is like a gym membership you never use: looks virtuous, accomplishes nothing, eventually hurts your back.

But maybe it’s not even about trade. Maybe this is more of a consistent reaction from a dominant power threatened by a rising power.

Whether led by Trump or simply the prevailing mood in Washington, the world is clearly shifting toward a more fractured, competitive, less globalized future.

The rules are changing.

Act II has begun.

Fasten your seatbelt—and maybe stash a few gold coins, just in case.

Simon Chan and Tara Mulia

Admin heyokha

Share

When the U.S. Dollar Index (DXY) dipped below the psychologically sacred 100 mark, the reaction across markets was immediate and biblical.

Bond yields erupted like a volcano no one had prepared an evacuation plan for.

Volatility rose sharply — not quite “end of the world” levels, but just enough to make traders double their coffee intake and triple-check their hedges.

Gold? Gold didn’t just rise — it strapped on a superhero cape, crashed through a few ceilings, and started flexing in slow motion.

It was, by all appearances, chaos.

And yet, there I sat—having gone through my second matcha in hand—deeply preoccupied with trying to figure out why my toast had burned on only one side.

Because here’s the thing: this wasn’t a heart attack. It was more like a long-overdue jog.

The dollar, after decades of indulgence, is simply trying to slim down. And trimming trade deficits, like trimming body fat, follows the same rule:

- Consume less than you expend

In trade-speak, that means importing less (or exporting more).

- Shed excess weight naturally

A modestly weaker dollar makes U.S. goods cheaper abroad

- Rebalance energy

Domestic factories and payrolls pick up the workload that overseas suppliers had been shouldering.

In that light, a weaker dollar isn’t a breakdown—it’s the feedback loop of a country attempting a strategic reset.

And behind that adjustment lies a bigger story: the U.S., under a Trump 2.0 presidency, is re-evaluating decades of trade dogma—not out of theory, but necessity.

Trump 1.0: Big Talk, Smaller Follow-Through

When Donald Trump took office in 2017, he promised to tear up “unfair trade deals” faster than a kid opens birthday presents.

NAFTA got rebranded as USMCA. Tariffs were slapped on China. Economists panicked.

But in practice?

- The U.S. trade deficit actually grew, from $481 billion in 2016 to $679 billion in 2020.

- Manufacturing jobs saw a brief lift before the pandemic pulled the rug out.

- The Phase One deal with China delivered photo ops but little systemic change.

Trump 1.0 was loud—but left the deeper structural incentives for offshoring intact.

Meanwhile, global rivals like China played a very different game.

The Richman Perspective: Free Trade’s Fine Print

Enter Balanced Trade (2014), by Jesse, Howard, and Raymond Richman.

We don’t quote it because it’s gospel—but because it captures how the U.S. might be viewing its predicament.

The Richmans argued that textbook free trade assumes everyone plays fair. But when countries embrace mercantilism, the game breaks.

Their key points:

- The U.S. hasn’t posted a goods & services surplus since 1976.

- Foreign reserves ballooned from $1.4 trillion (1995) to over $10 trillion (2013).

- America’s net international investment position flipped from +13% (1980) to –35% (2012).

And what’s more concerning: countries like China and Japan don’t spend those dollars on U.S. goods—they buy U.S. debt. As of early 2025, China holds $784.3 billion in Treasuries; Japan, $1.13 trillion. According to the Richmans, that’s not trade – that’s America exporting IOUs.

The Richmans suggest a “scaled tariff”—a self-adjusting levy pegged to bilateral deficits. Not protectionism per se, just a nudge to restore balance.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis; U.S. International Trade in Goods and Service

But again, this is a lens, not the truth. And maybe that’s the deeper takeaway as written by this book:

The U.S. isn’t declaring trade broken—it’s trying to restore competitiveness in a world where others stopped playing by the book long ago.

Trump 2.0: Trade Policy With a Bit More Teeth

Fast-forward to today: Trump 2.0 is leaning hard into so-called “reciprocity”.

Not just at rallies, but across a Washington that’s increasingly skeptical of free-market purity.

What’s on the table:

- Targeted tariffs based on bilateral trade deficits.

- Challenges to WTO rules that limit U.S. retaliation.

- Industrial policy tied to national security, encouraging onshoring of critical supply chains.

Of course, nothing is free.

A Brookings Institution report estimated that the 2018–2019 tariffs cost American consumers $57 billion a year. But for many voters—and policymakers—some level of sacrifice now feels worth it.

Globalization might have been a perfectly beautiful idea, but according to the Richmans, it is far from perfect in reality.

Global Reverberations: Some Win, Some Whimper

If the U.S. doubles down on “balanced trade,” ripple effects will follow.

Potential Winners:

- Emerging markets: India, Vietnam, Mexico—likely alternatives to China in the new supply chain map.

- Commodities: Reshoring means higher demand for industrial metals, energy, and logistics.

- Selective U.S. sectors: Tech, pharma, and defense-related manufacturing.

Likely Losers:

- Export-reliant economies like Germany, South Korea, and Japan.

- Global investors navigating rising FX and bond volatility.

The IMF warns: if tariffs become widespread, global GDP could shrink by 0.5%.

Not world-ending, but not nothing either.

Food for Thought: Was Free Trade Ever Really Free?

The Trump 2.0 shift isn’t just about tariffs—it’s a symptom of deeper anxieties:

- If globalization weakens national resilience, is it still worth it?

- Can you really have fair trade, and what does fair trade rhetorically even really mean?

- Is consumption-driven growth sustainable when you’ve outsourced everything?

The Richmans’ thesis? Free trade without balance is like a gym membership you never use: looks virtuous, accomplishes nothing, eventually hurts your back.

But maybe it’s not even about trade. Maybe this is more of a consistent reaction from a dominant power threatened by a rising power.

Whether led by Trump or simply the prevailing mood in Washington, the world is clearly shifting toward a more fractured, competitive, less globalized future.

The rules are changing.

Act II has begun.

Fasten your seatbelt—and maybe stash a few gold coins, just in case.

Simon Chan and Tara Mulia

Admin heyokha

Share