The Alchemy of Gold

The Alchemy of Gold

Reading The New Case for Gold, we came across one very interesting chapter where the author James Rickards discussed a BBC interview with Andrea Sella, a professor of chemistry at University College London.

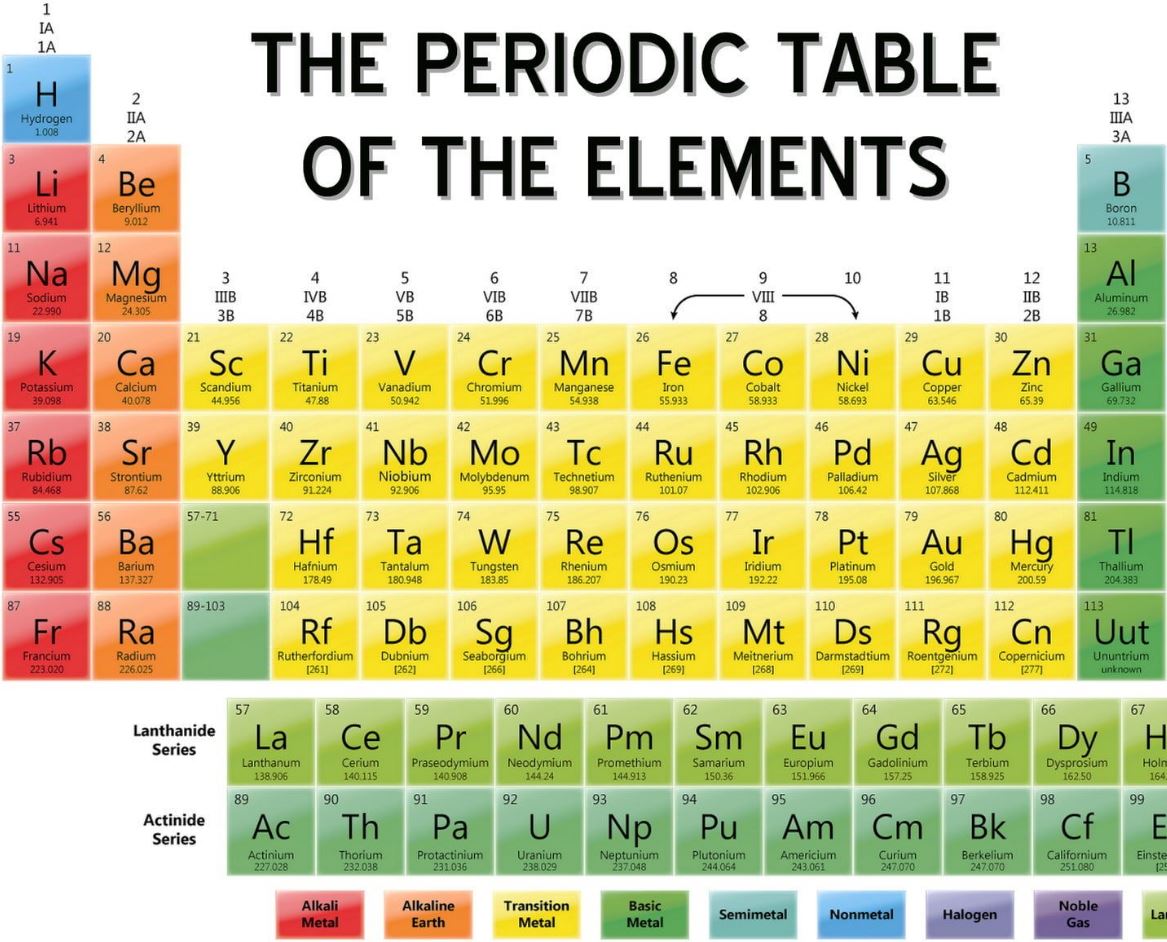

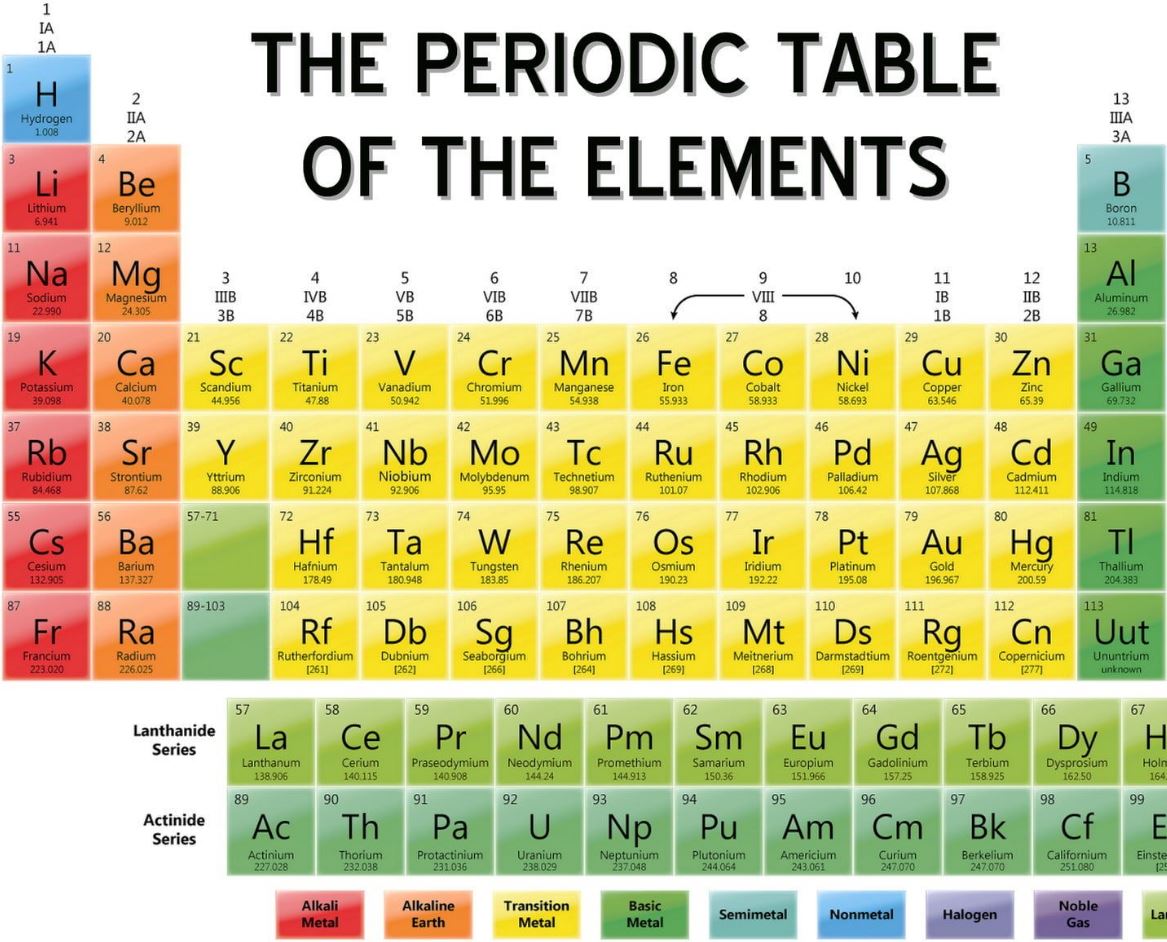

Prof Sella provided an in-depth review of the periodic table of the elements to explain why gold, among all the atomic structures in the known universe, is uniquely and ideally suited to be money in the physical world.

We can (rather painfully) recall the periodic table of the elements from high school chemistry class. A total of 118 elements are represented, from hydro-gen (atomic number 1) to ununoctium (# 118). Nothing physical in the known universe that is not made of one of these elements or a molecular combination. If we are looking for money, we will find it here.

Prof Sella quickly dismissed ten elements on the right-hand side of the table, including helium (He), argon (Ar), and neon (Ne). They are all gases at room temperature and would literally float away. Clearly not good as money.

Elements such as mercury (Hg) and bromine (Br) are liquid at room temperature, so they are all out. Arsenic (As) is rejected for a very obvious reason: because not everyone is convinced that money is poison. Turning to the left-hand side of the periodic table, we get twelve alkaline elements. The problem is that they dissolve or explode on contact with water. Saving money for a rainy day is a good idea, but not if the money dissolves when it rains.

The next elements to be discarded are those of Uranium (U), Plutonium (Pu), and Thorium (Th), for the simple reason that they are radioactive. Also included in this group are thirty radioactive ele-ments made only in labs that decompose moments after they are created.

Most other elements are also unsuitable as money. Iron (Fe), copper (Cu), and lead (Pb) don’t make the final cut because they rust or corrode. No one wants money that debases itself, we should leave the debasement business to the central bankers.

Aluminium (Al) is too flimsy and Titanium (Ti) is too hard to smelt. With this process of elimination, there are only eight candidates left for use as money: the noble metals. While all of them are rare, only gold and silver are available in sufficient quan-tities to make a practical money supply. The rest are too rare.

Thus, only two elements, silver and gold, left. Both are scarce but not impossibly rare. Both also have a relatively low melting point and are therefore easy to turn into coins, ingots, and jewellery. Out of these two, silver reacts with minute amounts of sulphur in the air.

Also, gold (Au) has one final attraction: it’s golden. All of the other metals are silvery in co-lour, except copper which turns green when exposed to air.

Admin heyokha

Share

Reading The New Case for Gold, we came across one very interesting chapter where the author James Rickards discussed a BBC interview with Andrea Sella, a professor of chemistry at University College London.

Prof Sella provided an in-depth review of the periodic table of the elements to explain why gold, among all the atomic structures in the known universe, is uniquely and ideally suited to be money in the physical world.

We can (rather painfully) recall the periodic table of the elements from high school chemistry class. A total of 118 elements are represented, from hydro-gen (atomic number 1) to ununoctium (# 118). Nothing physical in the known universe that is not made of one of these elements or a molecular combination. If we are looking for money, we will find it here.

Prof Sella quickly dismissed ten elements on the right-hand side of the table, including helium (He), argon (Ar), and neon (Ne). They are all gases at room temperature and would literally float away. Clearly not good as money.

Elements such as mercury (Hg) and bromine (Br) are liquid at room temperature, so they are all out. Arsenic (As) is rejected for a very obvious reason: because not everyone is convinced that money is poison. Turning to the left-hand side of the periodic table, we get twelve alkaline elements. The problem is that they dissolve or explode on contact with water. Saving money for a rainy day is a good idea, but not if the money dissolves when it rains.

The next elements to be discarded are those of Uranium (U), Plutonium (Pu), and Thorium (Th), for the simple reason that they are radioactive. Also included in this group are thirty radioactive ele-ments made only in labs that decompose moments after they are created.

Most other elements are also unsuitable as money. Iron (Fe), copper (Cu), and lead (Pb) don’t make the final cut because they rust or corrode. No one wants money that debases itself, we should leave the debasement business to the central bankers.

Aluminium (Al) is too flimsy and Titanium (Ti) is too hard to smelt. With this process of elimination, there are only eight candidates left for use as money: the noble metals. While all of them are rare, only gold and silver are available in sufficient quan-tities to make a practical money supply. The rest are too rare.

Thus, only two elements, silver and gold, left. Both are scarce but not impossibly rare. Both also have a relatively low melting point and are therefore easy to turn into coins, ingots, and jewellery. Out of these two, silver reacts with minute amounts of sulphur in the air.

Also, gold (Au) has one final attraction: it’s golden. All of the other metals are silvery in co-lour, except copper which turns green when exposed to air.

Admin heyokha

Share