The AI Power Grab: Why Aluminum is Now a Zero Sum Game for Electrons

The AI Power Grab: Why Aluminum is Now a Zero Sum Game for Electrons

As we established in last week’s blog, the structural deficit in aluminum is widening, and the era of infinite, elastic supply is dead. We broke down China’s 45 million tonne production cap and the crumbling Western industrial base.

But to truly understand where this market is heading, we must ignore the metal itself. We need to look at the power plug.

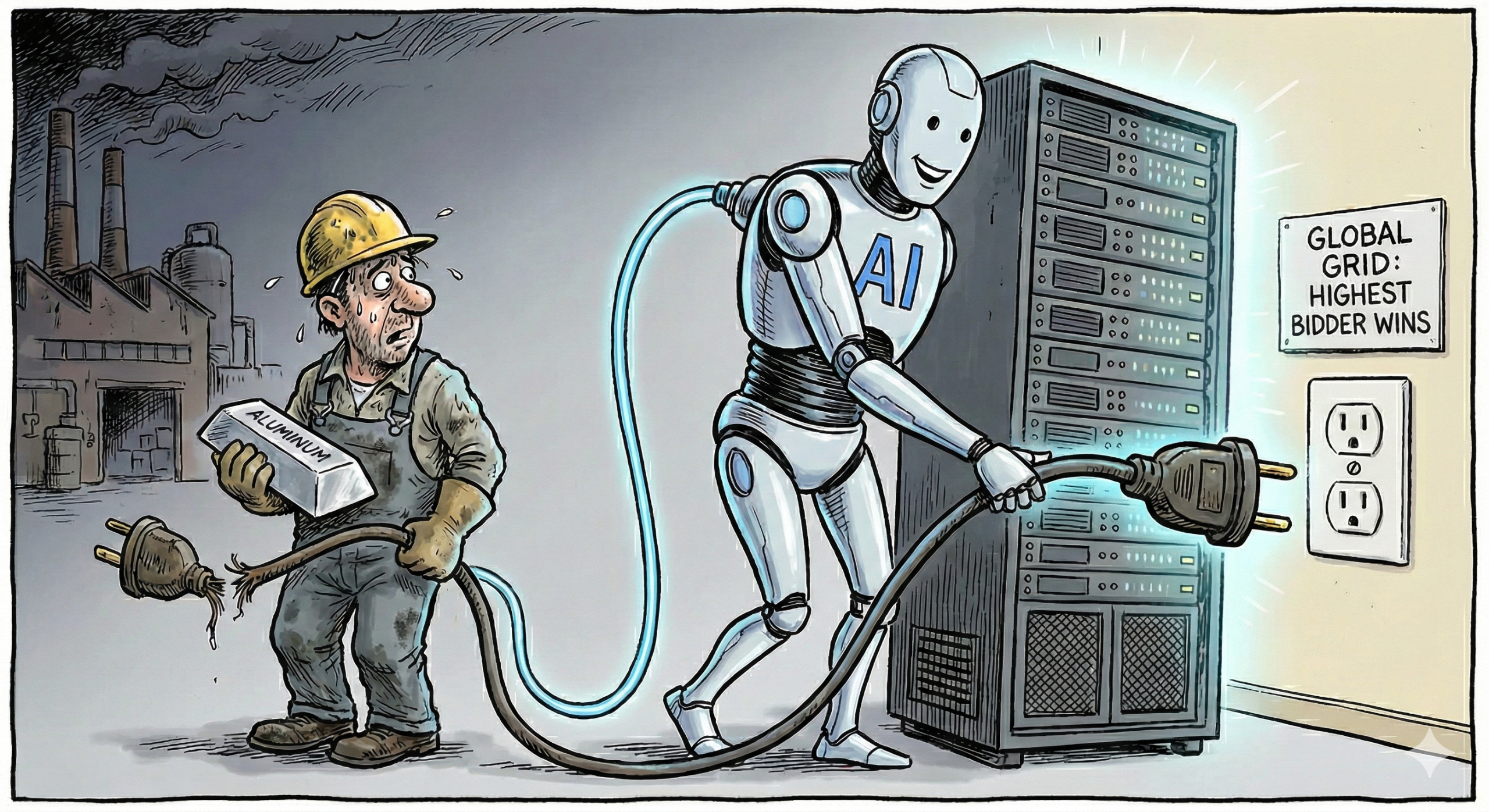

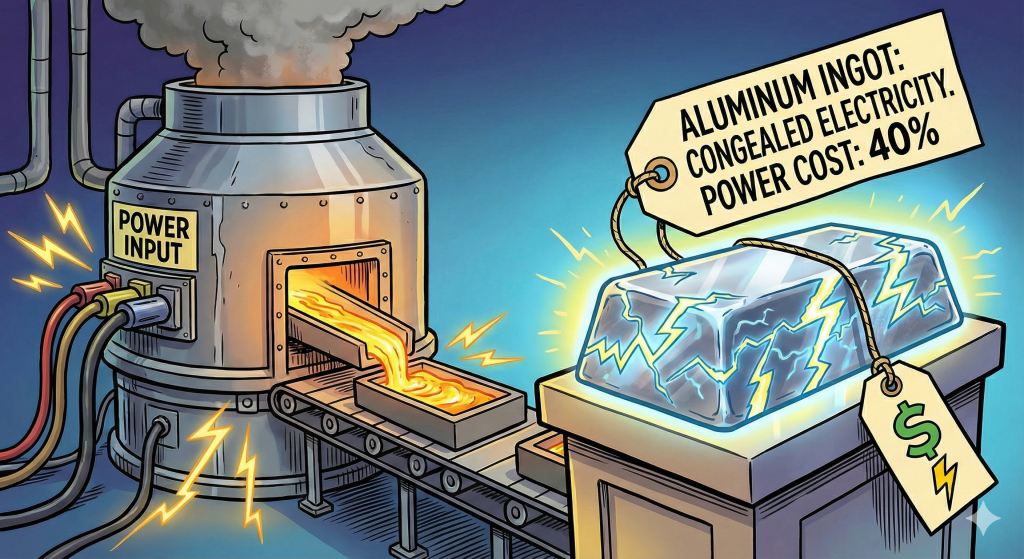

The Physics of “Congealed Electricity”

Most people miss the fundamental physics of this industry. Aluminum is not just a metal; it is effectively “congealed electricity.”

Power accounts for 30% to 40% of the total production cost of a single ingot. With global demand for the metal growing at 3% to 4% annually, the world requires an extra two million tonnes of metal every single year just to maintain the status quo.

To manufacture that extra metal, we need to add 3 to 4 gigawatts of continuous, baseload power to the grid annually. That is roughly the energy output of three to four nuclear reactors, or 15 to 20 massive data center campuses, running 24/7 forever.

The math is brutal. If we do not build the power plants, we cannot build the metal. In the past, we solved this by simply building more power generation. Today, that new power is being diverted to a much wealthier buyer.

The Auction for the Grid

We are witnessing a direct auction for grid capacity that aluminum producers mathematically cannot win.

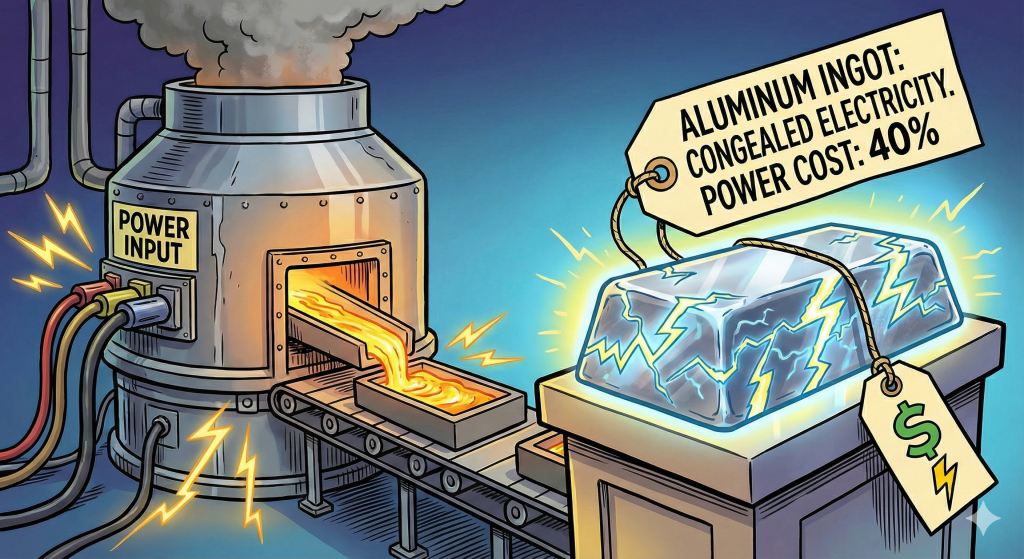

High electricity costs are not a future risk; they are the root cause of the current devastation across the primary aluminum sector. Look at the recent casualties. Century’s Hawesville facility in Kentucky and Magnitude 7’s New Madrid smelter in Missouri did not shut down because of a lack of demand. They died because they failed to secure long term, competitively priced power deals and were forced into the day ahead spot market.

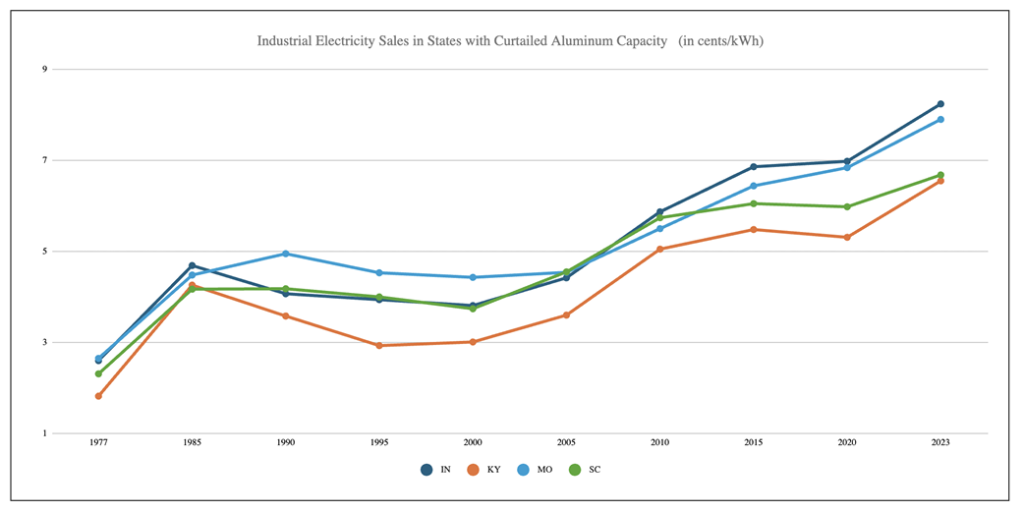

Historical timeline where Aluminum smelters closed coinciding when energy prices rose in select states

Source: The Aluminum Association and Energy Information Administration

Data from the Energy Information Administration paints a grim picture. In states that have seen their primary aluminum capacity permanently idled or completely gutted, power prices have marched relentlessly upward. Because power is the second largest component of total operating costs, a primary aluminum producer requires fixed costs to survive. A 20 year, competitively priced power contract is a strict prerequisite for securing any project financing. Without it, a smelter is dead on arrival.

But securing those long term contracts is now nearly impossible because a new apex predator has entered the market.

Competition for power between traditional manufacturing and the tech sector is not a fair fight. Data center demand is entirely price inelastic. Recent market transactions prove that tech hyperscalers effectively have no limit on what they are prepared to pay for dependable, 24/7 baseload electricity. Because reliability is everything for their models, they are happily paying premiums of up to $100 per megawatt hour to secure guaranteed supply.

A smelter begins to bleed out if power prices rise above $40 per megawatt hour. Now, compare that to the tech industry. Microsoft recently struck a deal with Constellation Energy to resurrect Unit 1 of the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania. Analysts estimate Microsoft conceded to a staggering $110 to $115 per megawatt hour over 20 years. That is an 80% to 90% premium over intermittent renewables in the same region, and it completely prices out any industrial competitor. Meta is executing the exact same playbook, locking up nuclear power from the Clinton Clean Energy Center in Illinois for two decades at an estimated $80 to $85 per megawatt hour.

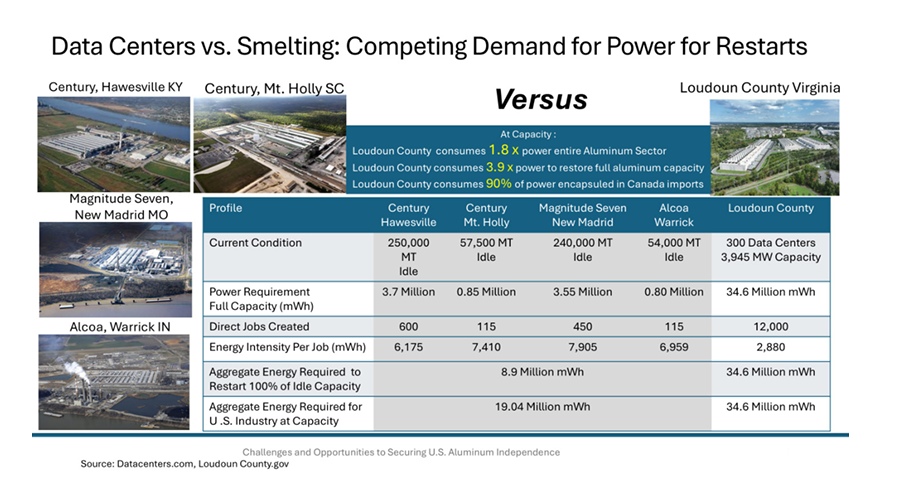

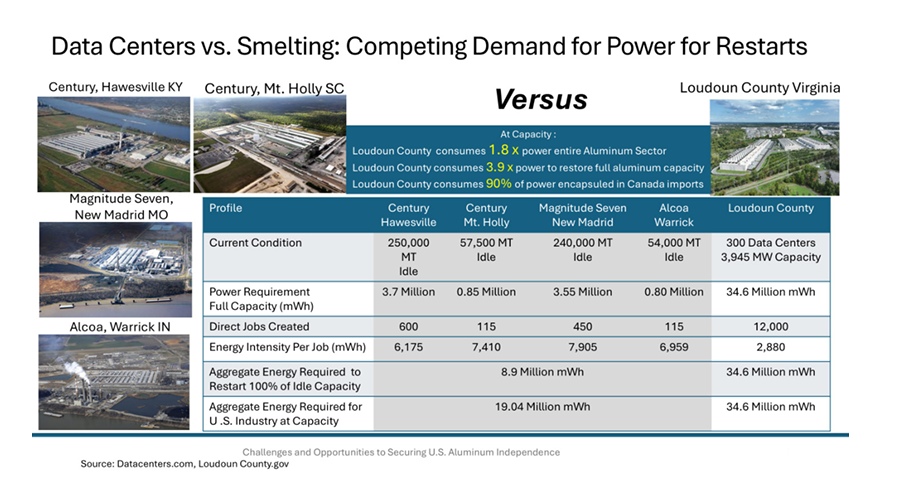

Data centers consume much more energy than aluminum. Would more focus and energy be given to the aluminum or on data centers?

Source: The Aluminum Association

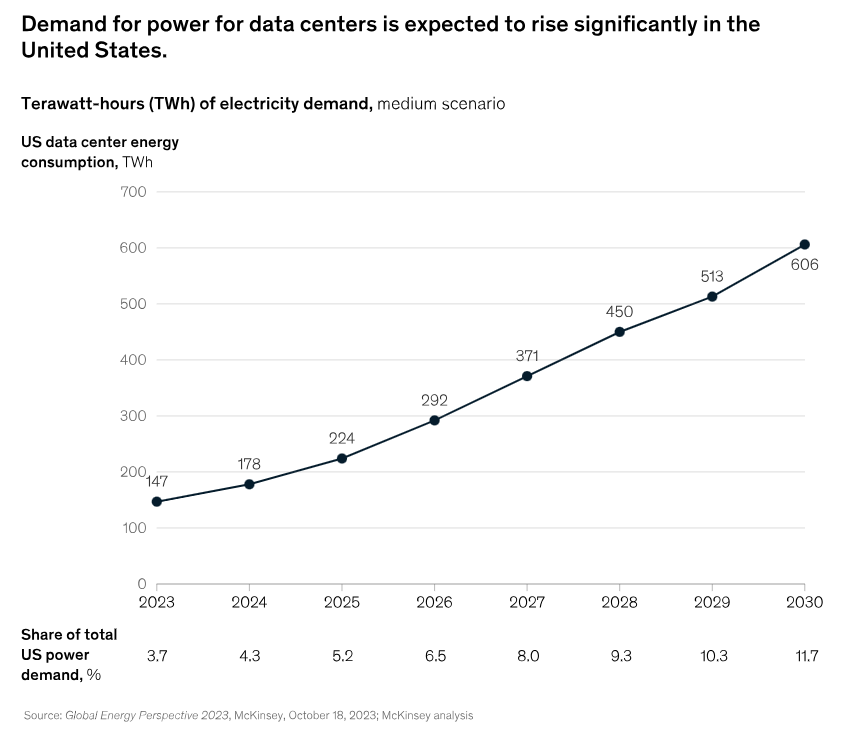

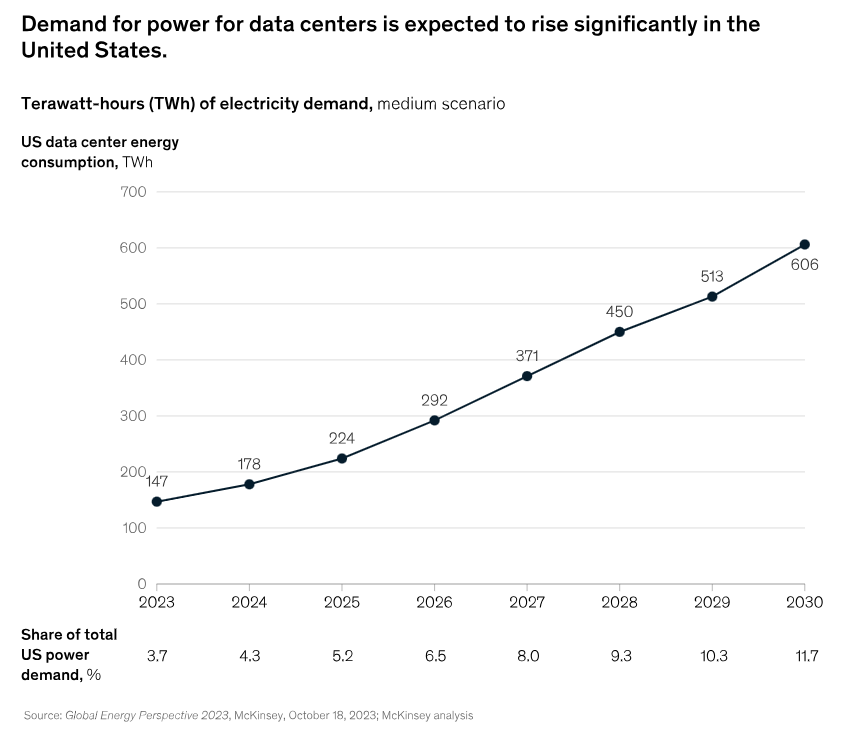

Smelters are being priced out of the grid. McKinsey projects that U.S. data center electricity demand will triple over the next five years, jumping from roughly 3% of total consumption today to nearly 12% by 2030. To replace the roughly 4.8 million metric tons of aluminum the U.S. imports in 2023 with domestic smelting capacity, the country would need to generate 71 terawatt hours of dedicated, continuous power annually. To put that scale into perspective, that is the equivalent output of more than 15 Hoover Dams, or the entire annual power consumption of the state of Minnesota.

Source: McKinsey

In a constrained grid, governments and utility companies will always prioritize the high margin, national security imperatives of AI over industrial smelting. But this creates a glaring paradox: if Big Tech buys up all the power, where will they source the physical metal to build their own infrastructure?

The auction heavily favors tech today, but it leaves us with a critical open question. Will this bidding war eventually break the physical supply chain, or will policymakers be forced to step in and subsidize the exact metal required to keep the AI revolution running?

The Investor Takeaway: Buy the Energy Privilege

The era of cheap metal is over. As these structural deficits take hold, the market is bracing for a period of extreme volatility and sustained upward pressure on prices.

The winners in this cycle will not just be the companies with the best bauxite mines; they will be the producers who possess moats that insulate them from the global energy bidding war. In this environment, the metal itself is secondary. The real asset is the energy contract.

Tara Mulia

For more blogs like these, subscribe to our newsletter here!

Admin heyokha

Share

As we established in last week’s blog, the structural deficit in aluminum is widening, and the era of infinite, elastic supply is dead. We broke down China’s 45 million tonne production cap and the crumbling Western industrial base.

But to truly understand where this market is heading, we must ignore the metal itself. We need to look at the power plug.

The Physics of “Congealed Electricity”

Most people miss the fundamental physics of this industry. Aluminum is not just a metal; it is effectively “congealed electricity.”

Power accounts for 30% to 40% of the total production cost of a single ingot. With global demand for the metal growing at 3% to 4% annually, the world requires an extra two million tonnes of metal every single year just to maintain the status quo.

To manufacture that extra metal, we need to add 3 to 4 gigawatts of continuous, baseload power to the grid annually. That is roughly the energy output of three to four nuclear reactors, or 15 to 20 massive data center campuses, running 24/7 forever.

The math is brutal. If we do not build the power plants, we cannot build the metal. In the past, we solved this by simply building more power generation. Today, that new power is being diverted to a much wealthier buyer.

The Auction for the Grid

We are witnessing a direct auction for grid capacity that aluminum producers mathematically cannot win.

High electricity costs are not a future risk; they are the root cause of the current devastation across the primary aluminum sector. Look at the recent casualties. Century’s Hawesville facility in Kentucky and Magnitude 7’s New Madrid smelter in Missouri did not shut down because of a lack of demand. They died because they failed to secure long term, competitively priced power deals and were forced into the day ahead spot market.

Historical timeline where Aluminum smelters closed coinciding when energy prices rose in select states

Source: The Aluminum Association and Energy Information Administration

Data from the Energy Information Administration paints a grim picture. In states that have seen their primary aluminum capacity permanently idled or completely gutted, power prices have marched relentlessly upward. Because power is the second largest component of total operating costs, a primary aluminum producer requires fixed costs to survive. A 20 year, competitively priced power contract is a strict prerequisite for securing any project financing. Without it, a smelter is dead on arrival.

But securing those long term contracts is now nearly impossible because a new apex predator has entered the market.

Competition for power between traditional manufacturing and the tech sector is not a fair fight. Data center demand is entirely price inelastic. Recent market transactions prove that tech hyperscalers effectively have no limit on what they are prepared to pay for dependable, 24/7 baseload electricity. Because reliability is everything for their models, they are happily paying premiums of up to $100 per megawatt hour to secure guaranteed supply.

A smelter begins to bleed out if power prices rise above $40 per megawatt hour. Now, compare that to the tech industry. Microsoft recently struck a deal with Constellation Energy to resurrect Unit 1 of the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania. Analysts estimate Microsoft conceded to a staggering $110 to $115 per megawatt hour over 20 years. That is an 80% to 90% premium over intermittent renewables in the same region, and it completely prices out any industrial competitor. Meta is executing the exact same playbook, locking up nuclear power from the Clinton Clean Energy Center in Illinois for two decades at an estimated $80 to $85 per megawatt hour.

Data centers consume much more energy than aluminum. Would more focus and energy be given to the aluminum or on data centers?

Source: The Aluminum Association

Smelters are being priced out of the grid. McKinsey projects that U.S. data center electricity demand will triple over the next five years, jumping from roughly 3% of total consumption today to nearly 12% by 2030. To replace the roughly 4.8 million metric tons of aluminum the U.S. imports in 2023 with domestic smelting capacity, the country would need to generate 71 terawatt hours of dedicated, continuous power annually. To put that scale into perspective, that is the equivalent output of more than 15 Hoover Dams, or the entire annual power consumption of the state of Minnesota.

Source: McKinsey

In a constrained grid, governments and utility companies will always prioritize the high margin, national security imperatives of AI over industrial smelting. But this creates a glaring paradox: if Big Tech buys up all the power, where will they source the physical metal to build their own infrastructure?

The auction heavily favors tech today, but it leaves us with a critical open question. Will this bidding war eventually break the physical supply chain, or will policymakers be forced to step in and subsidize the exact metal required to keep the AI revolution running?

The Investor Takeaway: Buy the Energy Privilege

The era of cheap metal is over. As these structural deficits take hold, the market is bracing for a period of extreme volatility and sustained upward pressure on prices.

The winners in this cycle will not just be the companies with the best bauxite mines; they will be the producers who possess moats that insulate them from the global energy bidding war. In this environment, the metal itself is secondary. The real asset is the energy contract.

Tara Mulia

For more blogs like these, subscribe to our newsletter here!

Admin heyokha

Share