It has been a sobering, anxious week. When the geopolitical reality gets this dark, sometimes the only way to process the stress is to step back and find a sliver of humor in the sheer, chaotic absurdity of human behavior.

If you have ever wondered why that behavior feels so erratic lately, or why you can’t finish a movie without checking your phone, blame Mr. Beast.

In a December 2025 interview, Jimmy Donaldson, better known as the guy who gets 200 million views by burying himself alive or handing out islands, claimed that roughly 2% of all human time may now be spent on YouTube. He noted that to capture an American audience today, you actually have to make longer videos (pushing 25 to 30 minutes) to cut through the noise of TikTok’s doom-scrolling. But here is the catch: to keep people watching, the content has to be relentlessly fast-paced and constantly escalating. We have been trained to demand an adrenaline spike every five seconds.

Source: The New York Times, Youtube

We are officially living in the Goldfish Economy. Our collective attention span is shattered. We read the headline, skip the article, and trade the vibe.

Which brings me to the absolute comedy of the Indonesian stock market this week.

Over the weekend, the world watched with a knot in its stomach as tensions flared in the Middle East, with Iran launching drones and missiles toward Israel. It is a serious, complex crisis. The immediate, logical market fear was a disruption in the Strait of Hormuz, a critical chokepoint for global energy. Crude oil prices were expected to spike.

So, how did the highly sophisticated, incredibly focused retail investor process this heavy reality on Monday morning?

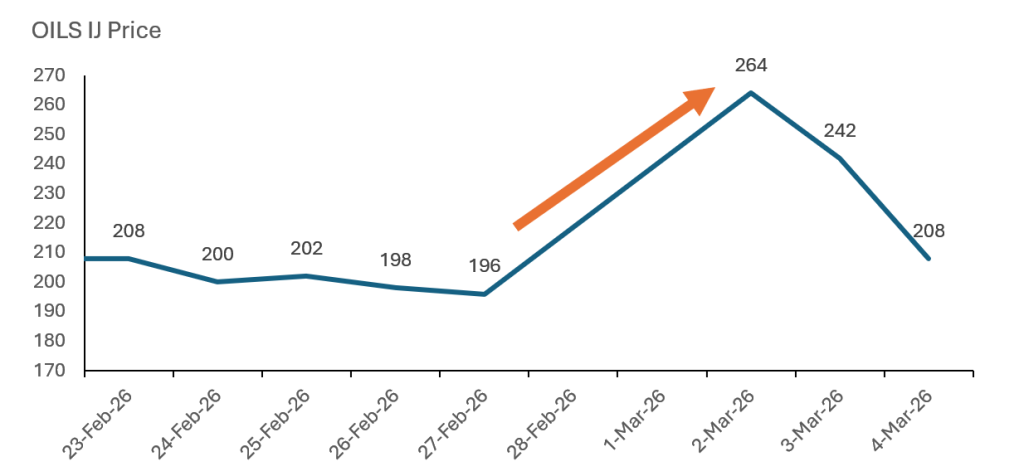

They panicked, opened their trading apps, seemed to search the word “OIL,” and aggressively bought the first ticker they saw: OILS IJ.

They bought it so fast and so hard that the stock hit its upper limit circuit breaker (Auto Reject Atas, or ARA) and nearly again the day after. The chart went vertical.

There is just one tiny, hilarious problem.

OILS IJ is the ticker for PT Indo Oil Perkasa Tbk.

They do not drill for crude oil. They do not have tankers in the Strait of Hormuz. They do not deal in fossil fuels at all.

OILS IJ refines coconut oil.

Geopolitics, powered by coconuts

Source; Bloomberg

Yes. In the face of a military conflict threatening global crude energy supplies, day traders blindly panic-bought a company that makes the stuff you use to fry tempeh and make your hair shiny. It is the purest distillation of the Mr. Beast era. No one read the prospectus. No one checked the underlying business. They saw a scary headline, matched the word “oil” to a ticker, and smashed the buy button before their attention drifted to a 15-second video of a cat doing a backflip.

But before we laugh too hard at the retail crowd hoarding coconut oil, we have to admit: the Goldfish Economy infects the big leagues, too.

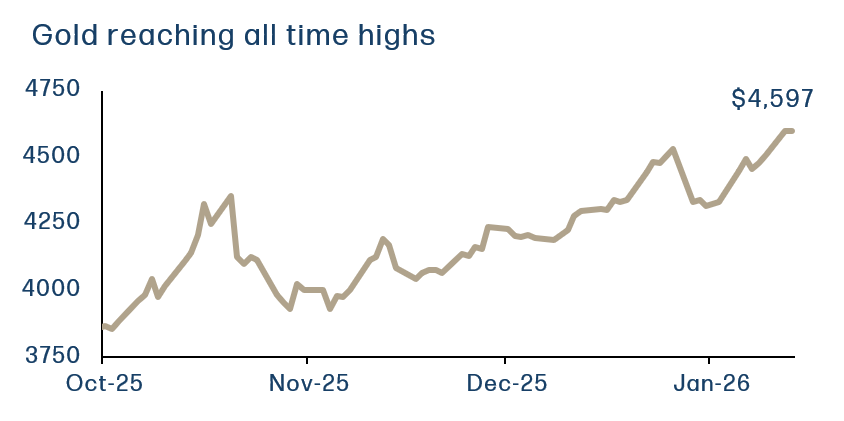

Knee-jerk reactions are the new global standard. Look at what happened to gold this very same week.

The V-shape recovery of institutional attention spans

Source: Bloomberg

On the exact same geopolitical noise, algorithms and institutional panic-sellers momentarily lost their minds. They aggressively flushed the ultimate safe-haven asset, sending gold plunging down below $5,050 an ounce in a vicious, split-second shakeout.

And then? The attention span reset. The market remembered what physical metal actually is, and the price violently slingshot right back up, settling comfortably back above $5,130.

It was a classic algorithmic head-fake, a trap perfectly designed for a market running on a 15-second attention span.

This is the reality of investing today. Whether it is a coconut oil company surging on a literal misunderstanding or gold momentarily plunging on algorithmic panic, the market is built to shake out the impatient.

The edge no longer goes to the fastest trader. It goes to the one who can actually sit still, read the fine print, and outlast the panic.

Tara Mulia

For more blogs like these, subscribe to our newsletter here!

Admin heyokha

Share

It has been a sobering, anxious week. When the geopolitical reality gets this dark, sometimes the only way to process the stress is to step back and find a sliver of humor in the sheer, chaotic absurdity of human behavior.

If you have ever wondered why that behavior feels so erratic lately, or why you can’t finish a movie without checking your phone, blame Mr. Beast.

In a December 2025 interview, Jimmy Donaldson, better known as the guy who gets 200 million views by burying himself alive or handing out islands, claimed that roughly 2% of all human time may now be spent on YouTube. He noted that to capture an American audience today, you actually have to make longer videos (pushing 25 to 30 minutes) to cut through the noise of TikTok’s doom-scrolling. But here is the catch: to keep people watching, the content has to be relentlessly fast-paced and constantly escalating. We have been trained to demand an adrenaline spike every five seconds.

Source: The New York Times, Youtube

We are officially living in the Goldfish Economy. Our collective attention span is shattered. We read the headline, skip the article, and trade the vibe.

Which brings me to the absolute comedy of the Indonesian stock market this week.

Over the weekend, the world watched with a knot in its stomach as tensions flared in the Middle East, with Iran launching drones and missiles toward Israel. It is a serious, complex crisis. The immediate, logical market fear was a disruption in the Strait of Hormuz, a critical chokepoint for global energy. Crude oil prices were expected to spike.

So, how did the highly sophisticated, incredibly focused retail investor process this heavy reality on Monday morning?

They panicked, opened their trading apps, seemed to search the word “OIL,” and aggressively bought the first ticker they saw: OILS IJ.

They bought it so fast and so hard that the stock hit its upper limit circuit breaker (Auto Reject Atas, or ARA) and nearly again the day after. The chart went vertical.

There is just one tiny, hilarious problem.

OILS IJ is the ticker for PT Indo Oil Perkasa Tbk.

They do not drill for crude oil. They do not have tankers in the Strait of Hormuz. They do not deal in fossil fuels at all.

OILS IJ refines coconut oil.

Geopolitics, powered by coconuts

Source; Bloomberg

Yes. In the face of a military conflict threatening global crude energy supplies, day traders blindly panic-bought a company that makes the stuff you use to fry tempeh and make your hair shiny. It is the purest distillation of the Mr. Beast era. No one read the prospectus. No one checked the underlying business. They saw a scary headline, matched the word “oil” to a ticker, and smashed the buy button before their attention drifted to a 15-second video of a cat doing a backflip.

But before we laugh too hard at the retail crowd hoarding coconut oil, we have to admit: the Goldfish Economy infects the big leagues, too.

Knee-jerk reactions are the new global standard. Look at what happened to gold this very same week.

The V-shape recovery of institutional attention spans

Source: Bloomberg

On the exact same geopolitical noise, algorithms and institutional panic-sellers momentarily lost their minds. They aggressively flushed the ultimate safe-haven asset, sending gold plunging down below $5,050 an ounce in a vicious, split-second shakeout.

And then? The attention span reset. The market remembered what physical metal actually is, and the price violently slingshot right back up, settling comfortably back above $5,130.

It was a classic algorithmic head-fake, a trap perfectly designed for a market running on a 15-second attention span.

This is the reality of investing today. Whether it is a coconut oil company surging on a literal misunderstanding or gold momentarily plunging on algorithmic panic, the market is built to shake out the impatient.

The edge no longer goes to the fastest trader. It goes to the one who can actually sit still, read the fine print, and outlast the panic.

Tara Mulia

For more blogs like these, subscribe to our newsletter here!

Admin heyokha

Share